In “The Architectural Sacking of Paris” Claire Berlinski contributor of the magazine “City Journal” maintains that proposed urban developments in Paris will lead to the ruination of its classical beauty. This article comes from the perspective of being against virtually any modern developments and yet contains much valid information about what Paris currently is most loved for, which projects are underway, the city’s architectural history, its social and economical situation as well as some past modern projects and their impact on the city.

The focus of this research project is to address the gap that is common to a range of sources and how they see the modernisation of Paris. I have identified the gap as being that the problem with the changes may not be the modern building style, it may in fact be their scale: their height and their power to destroy an overall cityscape. Paris is known for its low cityscape and its single tower, the Eiffel Tower. Modern buildings are inevitable and have been applied on a low scale within Paris and other historical European cities in a tasteful and respectful manner without spoiling cityscapes. These elements of modernisation add to the cities modern history, respecting the overall cityscape of Paris and creating new landmarks such as the Centre Pompidou, Grande Arche de la Défense, the Louis Vuitton Foundation by Frank Gehry and the glass triangle pyramid at the Louvre.

The question is not whether Paris should undergo architectural modernisation and “move forward” but rather, should there be stricter regulations on moving Paris into the 21st Century in a respectful manner, maintaining its 19th Century appeal that the many millions of tourists come to visit. Are high rise buildings a stab in the heart of France’s cultural identity?

Various research methods have been used to write this essay. I have visited the Architectural Museum at the University of South Australia for archived information and images where I found an essay written by Julie Collins about Adelaide, a city also facing the emergence of high-rise buildings. I read books written during the time of Paris’s early modernisation and urban planning, and texts with views for and against modern buildings expressing opinions regarding their role in modern urban development. Official websites and video interviews with Nicolas Sarkozy have informed me about the Grand Paris project and websites of the architectural firms behind the high-rises explain why they find it acceptable to build some controversial buildings. My personal experience visiting Paris, London, Rome, Florence and Berlin this year enabled me to compare the cities landscape, noticing which cities were affected by high-rises and how some had clearly strict restrictions, both in height and heritage protection. Additionally, Government websites inform me about European height restrictions.

A Traditionalist City Facing Modernisation

The Traditional City

Paris is a city that is made up of historical buildings from the period of the Middle Ages to the 21st Century set in a classical urban landscape. Commissioned by Emperor Napoleon III during the 19th Century, Baron Georges Eugène Haussmann was instructed to remodel Paris to “aérer, unifier, et embellir”, to let the city “breathe, unite and to be embellished.” This city is now the most visited city in the world. Paris is a city of romance, tradition and charm. Painting the scene author Claire Berlinski, in her article “The Architectural Sacking of Paris” describes Paris as

“One where wide, tree-lined boulevards lead the eye to neoclassical monuments, to grand mansions made of cream marble and limestone, to spectacular fountains and manicured gardens. The great cathedrals became the jewels in an urban charm bracelet of gilded statues, golden ornaments, winking gargoyles, flirtatious nymphs, and pudgy cherubs. In the evening, moonlight sparkles over the gossamer spires and steeples and glitters in the Seine; where young lovers gather on the arched bridges.”

A New Plan

Paris is also a city facing economic growth and part of the modernisation plan is to build towering high-rise buildings dominating the current classical low-rise cityscape. These buildings are part of a larger plan, the 35-Billion-Dollar Grand Paris project, “The Greater Paris”, sometimes translated as “The Great Bet”.

Until he took office, President Nicolas Sarkozy of France never seemed destined to be a patron of architecture. In the weeks leading up to his election, more than a few architects I spoke with in Paris disparaged him as “the American,” a reference to his supposed lowbrow cultural tastes. But the French presidency has a way of infecting its occupant with visions of architectural grandeur. Georges Pompidou is better remembered today for the elaborate populist structure that bears his name than for his Gaullist policies. François Mitterrand created nearly a dozen new monuments in Paris, including I. M. Pei’s glass pyramid at the Louvre, a gigantic new national library and the Bastille Opera House. And now Sarkozy seems determined to outdo even Mitterrand.

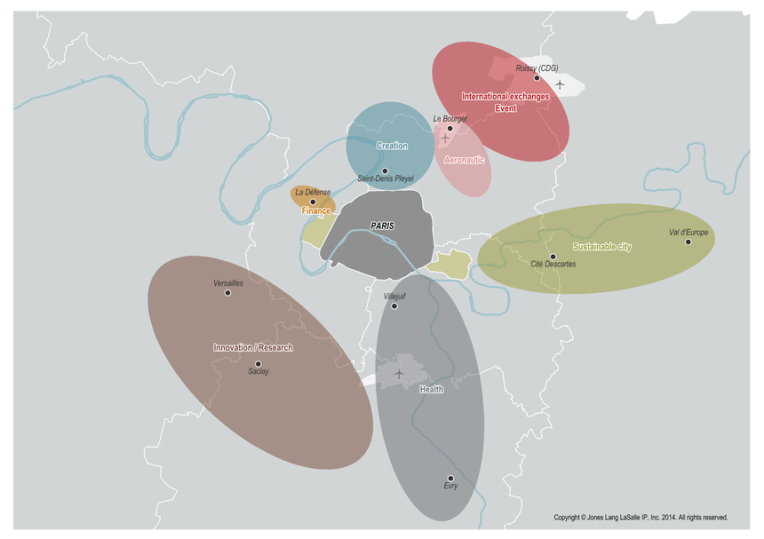

This plan was created during 2007, by President Nicolas Sarkozy to transform the Paris metropolitan area into a major 21st century European metropolis. The project’s official website “JLL Grand Paris” claims it will improve the living environment of the inhabitants, correct territorial inequalities, build a sustainable city and support economic growth. This project aims to expand Paris outwards creating strategic development centres in the form of seven territories (clusters) around the city centre for different types of businesses.

“Two million people live in the historic centre. The périphérique separates them like a moat from the 8 million who live, stacked atop one another, in the concrete-slab housing towers of the banlieues. Paris has exiled its poor and its immigrants to the ugly margins in a form of architectural apartheid. These buildings embody modernism’s failures. They are places, in the words of then–interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy, “where gangrene has set in.” Paris is still beautiful, but God knows the architects are doing their best to ruin it. The outskirts have been destroyed, and the centre has been compromised.”

Just like former President (1981 to 1995) Francois Mitterrand created some famous monuments including the Louvre Pyramid, new national library and the Bastille Opera House, President Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-2012) intended to leave his mark. On April 29, 2009 at the Architecture Museum in Paris, Sarkozy said in a speech “We cannot afford not to invest, and that applies to the Metropolis of Paris and to France as a whole.” He also said that his plan was to abolish suburbs in order that someone’s address will no longer be a matter for social discrimination.

Famous modernist London architect, Richard Rogers said that Sarkozy’s 2009 speech was:

“the best speech I have ever heard from any President, Sarkozy started with saying, I want to make architecture the centre of society, and a centre of Paris, I want to have a vision for the 21st Century, it doesn’t matter if it is high or low, it has to be beautiful.” Rogers added “ The President clearly embraces the future, the imagination, this is the most beautiful cities in the world but it is not frightened to live in the 21st Century, in Britain, he are still trying to fight the traditionalist and the modernist, they are still talking about styles, but here we are talking about the present and future about Paris.”

See Video here

A Contradicting Project

A more contradictory aspect of the plan was to encourage new high-rise developments such as hotels and shops in the centre of Paris, to accommodate the high level of tourism. These few buildings may be modern but more importantly they are tall and a single building can spoil an entire cityscape As Claire Berlinski says:

“these would not have been out of place in Miami, Dubai, Shanghai or Sydney. Only a handful of cities would such buildings make so sense. One of them is Paris.”

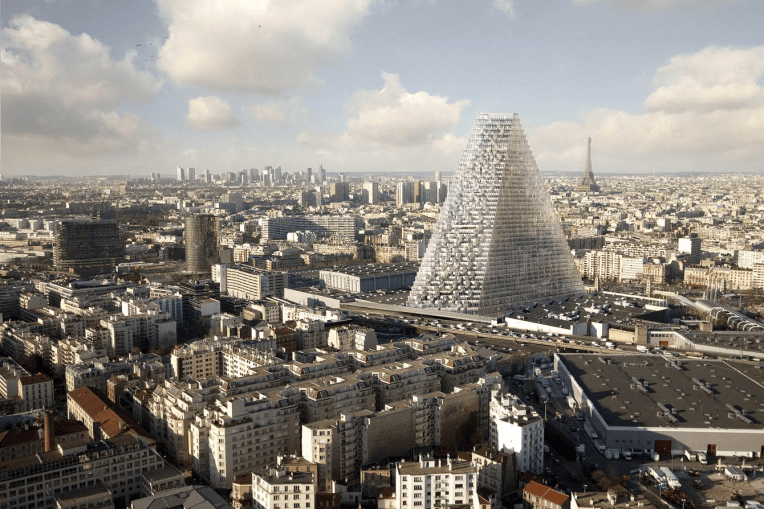

- Render of the Triangle Tower to be located on Porte de Versailles.

The Real Effect On Tourism And Way Of Living

In researching the different attitudes to the modernisation of Paris there seems to be a gap. Why would a plan with a focus on building outward in order not to disrupt and over crowd the inner city also allow the original, widely loved and cherished historical inner city to be affected? Paris is the most visited city in the world and not for the modern, sustainable, hi-tech, innovative high-rise buildings. It is for the Paris tourists all dream of, the old city of love and lights; the old Paris that is read in books or seen in pictures and movies. If these high-rise buildings destroy this image and the aesthetic appeal of historical landmarks that are an integral part of the urban landscape of Paris the resulting affect to tourism in this city could be devastating.

Today there are only two million in the city; the majority — eight million people — live in the banlieues. More than 100 years after Haussmann’s death, old Paris has become the world’s most elegant gated community — the sandblasted facades of its Haussmann-era buildings glistening with affluence. True, every now and then, a contemporary building is added. But this is mostly architectural fine-tuning. The city’s essential fabric remains the same.

It seems that Paris is made up of two cities, one historical and highly cultural city, with expensive housing, beautiful monuments, large perfect parks and elegant shops. Then there is the city of business and affordable housing set apart on the outskirts. Architecture critic from the New York Times, Nicolai Ouroussoff further describes these outskirts:

Meanwhile, just inside the Périphérique and beyond, is another Paris: a city of often dehumanizing public housing developments, concrete-slab office towers and arrested utopian schemes that embody many of Modernism’s failures. On some level, Sarkozy’s team of architects faces the same challenge Haussmann did 150 years ago: to give order to a vast, squalid, disordered metropolis that grew in fits and starts.

Modern buildings: are they really the problem?

While the notion of the Grand Paris project is positive and will aid in the reshaping of the urban pattern, improving the inner and outer city’s social and economic problems, there remains the issue of modern buildings emerging from the historical centre. In this essay the question asked is; is the problem modern buildings overall or more specifically the height of modern buildings?

Claire Berlinski has a strong negative opinion regarding any kind modern buildings in Paris. She even states that modern buildings

“send nearby property values plummeting, neighbourhood crime rockets and morbidity and mortality rates rise because drug dealers, pickpockets and voyous commute from the affordable outskirts of the city to loiter around the Pompidou Centre and other shiny modern buildings which scream expensive.”

While it is true that in my personal experience I have been approached by beggars while waiting in the queue at the Pompidou, there was no sense of danger or criminal activity. Her assertion that housing prices are plummeting and mortality rates rising is extreme and not supported by statistics.

A Modern Example

The famous modern buildings Berlinksi’s mentions are from 1985 when President Francois Mitterand started the project “Mitterand’s Grandes Operations d’Architecture et d’Urbanisme” to symbolize Socialist Party politics, and to exhibit France’s stature at the end of the twentieth century. These included the Louvre Pyramid, the Parc de la Villette, the Arab World Institute, the Opéra Bastille, the Grande Arche de la Défense, the Ministry of Finance, and the Bibliothèque Nationale.

In “The Architectural Sacking of Paris” the opinion is that:

Not only are these buildings ugly; they also do not succeed even in achieving the architects’ justification for the ugliness: originality. Consider, for example, the Louvre Pyramid, commissioned by Mitterrand in 1984, which now occupies the Napoleon courtyard that had been as empty as its original designers intended it to be. Seeking someone who by instinct and training would properly appreciate the uniquely French character of both the buildings and the urban landscape, the Mitterrand government inexplicably turned to the Chinese-American architect I. M. Pei. It evokes a sense of familiarity: it looks like an Apple store.

Architect I.M.Pei contemplated for four months before agreeing to design a modern piece of architecture in the middle of one of the world’s most celebrated art museums. The results were controversial.

“When I first showed the idea to the public, I would say 90 percent were against it,” Pei recounted in a PBS documentary. “The first year and a half was really hell. I couldn’t walk the streets of Paris without people looking at me as if to say: ‘There you go again. What are you doing here? What are you doing to our great Louvre?’ ” “I hoped the controversy would die down quickly,” says Pei. “Perhaps I was a little optimistic. But, you know, the choice of the pyramid was not some personal idiosyncrasy. Paris is a city of pyramids, from the time when Napoleon [after whom the court the pyramid rises from is named] became fascinated by Egyptian architecture, after his military campaign along the Nile.”

Today the pyramid is the most visited art museum in the world, winning the Twenty-Five Year Award, an annual award that recognizes a building “that has stood the test of time by embodying architectural excellence for 25 to 35 years.”

Maintaining the famous 19th Century cityscape

These famous modern buildings have been accepted by the public because they celebrate their historical surroundings, with tasteful design and careful consideration of their setting. When standing on top of the Arc de Triomphe as I did, none of these modern buildings spoiled the cityscape which has barely changed over the course of hundreds of years. It is evident that generally there has been consideration paid to the overall horizon of Paris.

La Tour Montparnasse

How one skyscraper spoilt the Paris skyline

An example of how high-rise buildings negatively impact Paris’s cityscape is the 59-story, 209m La Tour Montparnasse built in 1973, its arrival caused a public outcry demanding that the city Council set a height limit of 37m for new buildings within the city limits in 1977. This allowed Paris’ famous monuments – the Eiffel Tower, the Arc de Triomphe, the Basilica of Sacré-Coeur, Notre-Dame – to reign unchallenged.

“The Montparnasse Tower is particularly tragic in its effect upon the Jardin du Luxembourg, the most beautiful of urban gardens, a masterpiece of sensitive and inviting design. Its lawns, tree-lined promenades, and flower beds are carefully cultivated. It offers a charming little bois with outdoor restaurants, a reflecting pool where French children still push-stick little boats amid paddling ducks, an orchard of apple and pear trees, a vintage carousel, and a broad esplanade, inviting to lovers and picnickers. To the west of the garden are the stately buildings of the Senate, a museum, a gravel footpath, and labeled trees. Visible from every corner of the park, though, is the thing—the Montparnasse Tower. Roughly the height of the Eiffel Tower, it is still—for now—the only skyscraper in Paris.”

Criticism and controversy surrounding the Tour Montparnasse has endured for many years, in 2008 an international poll named the tower the world’s second ugliest building in the world. Recently, Anne Hidalgo Major of Paris and member of the Socialist Party unveiled a plan to give the building a 700 million euro “facelift” turning the area into the “Times Square of Paris”. Despite the outrage towards the tower, Paris has slowly allowed skyscrapers back into the city. Since 2010 buildings have been erected up to 50m in certain central areas and 180m (590ft) in the city’s outer areas.

Hight Restriction

The question is why Paris cannot continue to follow the strict height restriction that was enforced between 1977 and 2010. Neighbouring cities such as Rome, Florence and Athens have very strict height restrictions so as not to overshadow historical landmarks and spoil the cityscape. In Rome no building can be higher than St Peters Basilica and all modern buildings must be built on the outskirts of the city. Shops and malls are built inside old monuments to blend in. Similarly, Athens cannot accept buildings that surpass 12 floors that would block the view of the Parthenon and in Petersburg buildings must not surpass the Winter Palace.

Examples: Paris Without Strict Height Restrictions

Andrew Ayers, an architectural historian who has written about Paris’s architecture, believes:

“the beauty and richness of a city like Paris comes from the combined effect of lots of very small-scale buildings acting together.” They allow for a clear sight line to the Eiffel Tower and complement other monuments that define Paris architecturally, like Notre Dame and the Arc de Triomphe. Conversely, tall modern towers—like the Tour Triangle’s large, glass-fronted triangular plan—as Ayers puts it “interact with nothing but themselves.”

The architectural renders of designs in progress shown here, create a frightful image of the imposition of these modern buildings. The Tour Duo positioned close to the Sacre Coeur in Montmartre confuses the eye and spoils the famous landmark while the Hermitage Plaza, in the Défense District with other modern high-rises is of a disproportionate scale. Foster and Partners goal was to create the tallest building in Europe, but this kind of extreme scale seems inappropriate and disrespectful to the city. As Andrew Ayers says, they interact with nothing but themselves.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre makes an interesting comment about the scale of skyscrapers and how they are supposedly meant to help with population density:

“it is not just the banks of the Seine, which put Paris on the list as World Heritage Centre, but it is the idea of the scale of the whole city.” “Paris is a city that was developed in the nineteenth century as a city of just six floors,” and this is what has given it its value. “It is the most densely populated city: it is denser than New York thanks to its formula of just six floors.” “The idea of densification with height, this is a misconception.” “A tower, because it needs a lot of services, it needs parking, does not help to make a denser, compact city… This is not a good model. This is not the future.”

Outcome of the literature review

The research conducted to write this review maintains that modernisation in cities is universal, inevitable and valuable. However, there is a clear gap in the available existing research and literature written about this topic and this is regarding how modernisation is represented in current urban design. Texts on modernisation acknowledge that this is because there is a need to accommodate an expansion of population, economy and industry, but the problem is how this is being represented. Why is there so much consideration given to expansion without mentioning height restriction which is the major blot on the city’s historical urban landscape. It seems that none question whether there may be other ways to expand on a low-rise scale acknowledging how much high-rise buildings will negatively impact the city and its international cultural image. There was previously a height restriction of 37 metres, but this regulation has been loosened by new leaders of France, allowing the construction of unattractive high-rise buildings. This extreme large-scale construction leads to the rejection of ‘modernisation’ when it could be aesthetically embraced if only the restrictions were once again respected.